Bill Gates, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders all want the rich to pay more taxes, but Gates is saying what the Democratic candidates appear to be thinking: Go for the capital gains rate.

Gates, the billionaire co-founder of Microsoft Corp. and the world’s second-richest man, has suggested that an increase in the capital gains tax rate is the simplest and most direct way to target America’s wealth.

And tax experts say that’s essentially what Sens. Warren and Sanders, both seeking the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, are doing with her wealth tax and his expansion of the estate tax. They’re just packaging it in a way that’s easier to sell on the campaign trail.

Democratic tax proposals are simply a “stealth attack” on the preferential rate for capital gains, said Christopher Faricy, a political science professor focused on tax and inequality at Syracuse University.

The very wealthiest of taxpayers derive the bulk of their riches not from wages or salaries but from capital gains profits on investments in stocks, property or other assets. Unlike labor income, which is taxed at a top rate of 37 percent, profits on assets held for at least a year before being sold bear a top rate of 20 percent.

In 2018, nearly 69 percent, or more than $584 billion, of all long-term capital gains went to the top 1 percent of the 1.1 million wealthiest U.S. filers, according to the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. The richest Americans got the lion’s share, with the top 0.1 percent of the 110,000 wealthiest filers scoring more than three quarters of that total.

“Most of the wealth gap is due to capital gains,” said Mark Spiegel, who runs a small hedge fund at Stanphyl Capital Management. “Nobody’s earning $50 million in labor income.”

Warren’s “Ultra-Millionaire Tax” plan targets capital gains without saying so and taxes them differently. She would require the top 75,000 wealthiest U.S. households to pay an annual 2 percent levy on each dollar of net worth over $50 million. Billionaires would pay an additional 1 percent tax over that.

By going after accumulated wealth at death, Sanders also targets the fruits of capital gains with his proposal to dramatically expand the estate tax, including imposing a new 77 percent rate on the portion of estates worth more than $1 billion. His plan would also lower the threshold at which the estate tax kicks in, to more than $3.5 million from the current $11 million, a level doubled in the GOP 2017 tax overhaul, and impose a 45 percent rate on estates worth as much as $10 million.

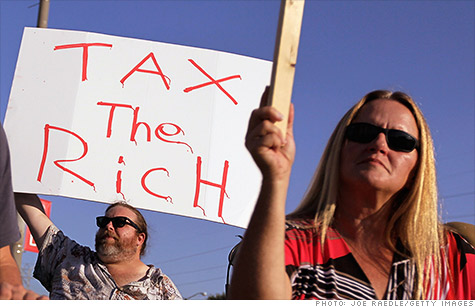

But going after capital gains has always been politically tricky and hard to sell to the public.

“Republicans treat” the capital gains tax benefit “like it’s a tablet from Moses,” said Mark Mazur, director of the tax policy center and a senior Treasury official during the Obama administration. “But there’s nothing sacred about it.”

Democratic plans that target wealth that largely comes from capital gains functionally serve as the equivalent of a higher rate on those profits, according to Mark Bloomfield, president and chief executive officer of the American Council for Capital Formation, a lobby and research group.

Said Andrew Hayashi, a tax law expert at the University of Virginia School of Law: “The spirit of the moment is that people feel like capital income is under-taxed.”

The Democrats’ proposals, derided as “socialism” by President Donald Trump, are most likely to remain just campaign rallying cries unless a Democrat wins the White House in 2020 and the party gains control of both houses of Congress.

But calls to seize the wealth of the top 1 percent or fewer make for better campaign rallies than calls to raise the rate on capital gains, Mazur said.

Gates, for what is believed to be the third time in a decade, said in a television interview last month that “the big fortunes, if your goal is to go after those, you have to take the capital gains tax, which is far lower at like 20 percent, and increase that.”

The revenue, he said, should be used to plug the budget deficit — a different goal from Democrats, who want to use the revenue raised on federal health and child care programs, among other things.

Political fights over capital gains aren’t new. But earlier battles focused directly on changing the rate itself, rather than targeting the fruits of those profits or indexing it for inflation — an idea that Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Trump briefly floated last year.

The capital gains rate has fluctuated from a high of nearly 40 percent in the late 1970s to 28 percent after former President Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts of 1986, and has been at the current 20 percent since 2013.

Gates hasn’t gone into detail on how to raise the capital gains rate. His $98.5 billion net worth includes the charitable Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. With nearly $51 billion in endowment assets as of the end of 2017, the foundation is fueled mainly by profits from Microsoft stock and dividends through Cascade Investment, his holding company.

Sign up for daily e-mail

Wake up to the day’s top news, delivered to your inbox