Rising prices are a serious problem, but so are the chronic challenges that the bill aims to confront.

The U.S. economy faces multiple challenges. The recovery has been more rapid than expected but now there’s an acute inflation problem. At the same time, the economy suffers from chronic problems, including underinvestment in children, insufficient support for working parents, and the threat of climate change. Addressing inflation is imperative, especially through less-expansionary monetary policy. But Congress must also address the chronic problems by passing the Build Back Better bill.

The current inflation has many causes, including a post-pandemic reallocation of labor, a spending shift from services to goods, lingering supply-chain disruptions, and rising global oil and gas prices. These international factors don’t tell the whole story. Inflation in the U.S. was similar to what the euro area experienced going into the pandemic, but prices have risen a cumulative 4% more in the U.S. over the past two years.

The oversize and poorly designed $2.7 trillion fiscal stimulus passed in December and March is at least partly to blame for the divergence. The Federal Reserve has continued de facto to loosen, with the Goldman Sachs Financial Conditions Index showing that the combination of lower long-term rates, higher stock prices and other financial changes has been the equivalent of more than a percentage point cut in the federal-funds rate since November 2020.

I expect inflation to be slower over the next year than it was over the past year. Still, it is likely to remain uncomfortably high. Demand will stay stronger than normal because consumers feel flush. The American Rescue Plan has roughly $500 billion to spend, and financial conditions are still loose. No one knows how long it will take to resolve problems with supply, but it would be foolish to count on a return to normal within the next year. Labor markets are tighter than ever, with seven unemployed workers for every 10 job openings, historically a more reliable predictor than the unemployment rate of the consumer-price index.

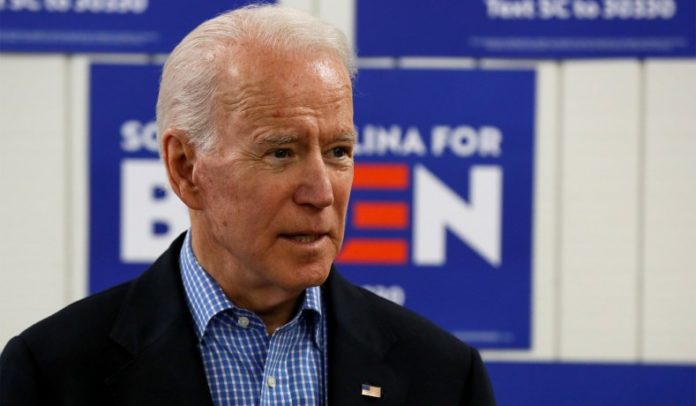

President Biden is doing what he should to address the microeconomic aspects of inflation: increasing capacity at ports, expanding microchip production and considering a release of raw materials from the National Defense Stockpile. The biggest lever he hasn’t pulled is a tariff reduction, especially on goods from China.

These steps, however, will have limited utility, because ultimately inflation is a macroeconomic problem. It’s the Fed’s job to keep it under control. No more wishful thinking that inflation is about to downshift dramatically. Policy makers at the Fed need to recognize that tools like asset purchases can’t solve the supply-side problems constraining U.S. labor markets and output. They have a dual mandate. They have to take inflation into account even if the economy isn’t yet at maximum employment.

The Fed has the right framework but needs better implementation. The central bank should express a more realistic understanding of inflation and firm up monetary policy by tapering its asset purchases more quickly. The Fed should set the default expectation that the federal-funds rate will be on an upward path starting in the first half of 2022 and that if employment or inflation is much lower than expected, the hikes will be slowed or canceled. Monetary policy would still be expansionary, but less so than it is now.

Build Back Better would have a minuscule impact on inflation over the medium and long term. It isn’t like previous rounds of stimulus. The money it spends would be spread out over time. It is mostly paid for by tax increases and some spending reductions, and includes investments that would enhance productivity. Moreover, as written, the bill’s default assumption is that long-term deficit will be reduced, leaving it up to Congress to let programs expire or find new offsets, like higher tax rates on high-income households and corporations, to continue them.

Even if this analysis is wrong and Build Back Better puts modest upward pressure on inflation, it would happen gradually. The Fed would have more than enough time, space and tools to keep inflation at whatever target it chooses. The potential short-term effects of Build Back Better on inflation are dwarfed by the good it would do.

Build Back Better would be a landmark step in permanently reducing child poverty. It would move the U.S. toward the widespread global practice of providing a child allowance to virtually all parents. It would also continue and expand the strong work incentives contained in the earned-income tax credit. Among developed countries, the U.S. has extremely low rates of preschool attendance and among the highest gross costs for child care, which can deter parents from working. Build Back Better would also make significant investments in combating climate change. The bill isn’t perfectly designed, but it’s a good start. Policy makers can evaluate its results and build on it over time.

Presidents aren’t elected to focus on only one problem, no matter how acute. President Lincoln didn’t focus solely on the Civil War; he also put considerable time and effort into establishing land-grant colleges and improving the financial system. Mr. Biden can walk and chew gum at the same time, continuing to focus on inflation while also helping to build a better, fairer and more sustainable economy for future generations. Now the Federal Reserve and Congress need to do their parts.

Mr. Furman, a professor of practice at Harvard, was chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, 2013-17.